Abercrombie & Fitch built an empire on exclusion.

CEO Mike Jeffries famously said they only wanted the “cool kids.” The stores were dark, loud, and heavily scented.

When I was a teenager, I remember the vibe. The Abercrombie & Fitch sweatshirts were mostly sported by popular jocks and cheerleaders. (How I got to wear one, I’m not sure.)

In a Netflix documentary, Jeffies says, “We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

The message couldn’t have been clearer: if you weren’t young, thin and beautiful, shop elsewhere.

Niching down is a smart strategy for most products, especially at first. You are the perfect fit for a very specific type of buyer. That type of person needs YOUR PRODUCT more than any other. Trying to attract everyone is way too imprecise, too ineffective and too expensive.

But for Abercrombie & Fitch, that exclusivity started to hurt. New players like H&M took advantage of the economic downturn and attracted a large number of those “cool kids.”

In 2016, Jeffries left A&F, and the brand did something radical. They fired their ideal customer.

The new Abercrombie welcomed everyone. Bigger sizes. Better lighting. Less cologne in the air. Sales soared.

It wasn’t the first time a brand deliberately alienated its original base:

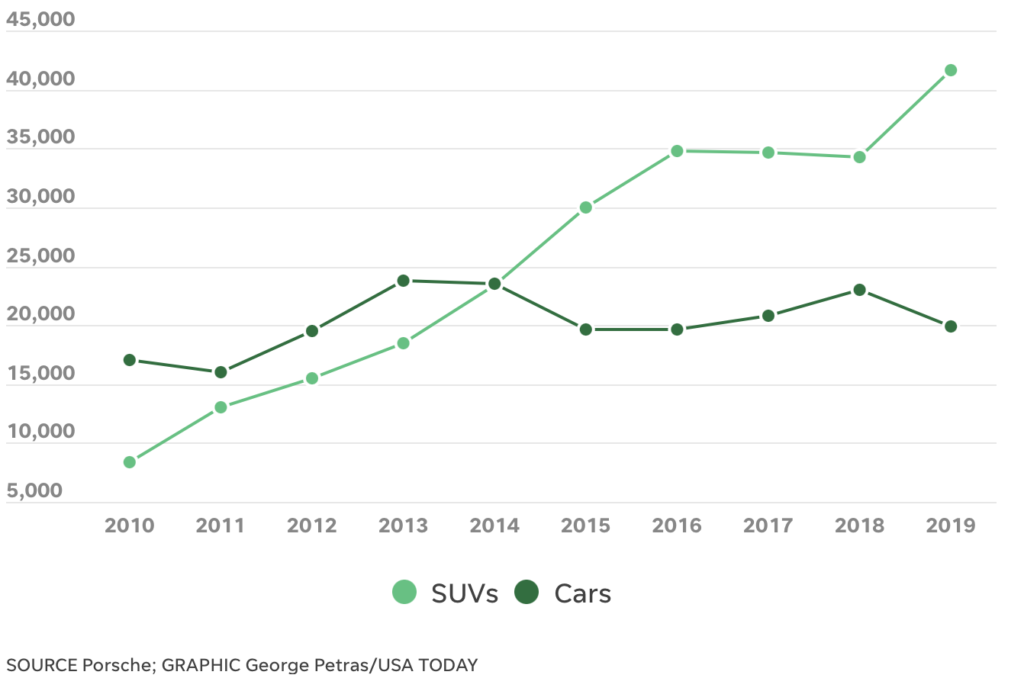

I also remember how Porsche purists were outraged when the Cayenne SUV launched. “Real” Porsches had two doors and the engine in back.

But SUV profits now fund the sports cars.

Burberry actively pushed away the “chavs” who’d embraced their check pattern, even discontinuing their baseball caps. And the luxury market returned.

And when Mercedes-Benz introduced lower-priced models, it horrified traditional Benz buyers. But the move helped Mercedes become the best-selling luxury car brand. (Now the pendulum is swinging the other way, with the focus on higher-end vehicles with bigger margins and fewer entry-level cars.)

I see similar things happening a lot lately.

Jaguar is doing exactly this with an unpopular rebrand — announcing they’re going all-electric by 2025 and shifting from “sporty luxury” to “modern luxury.” Essentially telling traditional V8-loving customers they’ll need to look elsewhere. Jag aficionados are raging and selling their cars. (But the reality: they were buying fewer and fewer. New buyers are needed.)

Then there’s Peloton‘s 2023-24 shift from luxury fitness brand to more accessible price points and mass market appeal (including selling on Amazon and Costco), potentially alienating their original exclusive customer base. Shareholders demand growth.

And Victoria’s Secret has gone through a complete transformation since 2021, firing the “Angels” and repositioning from male fantasy to female empowerment, replacing supermodels with activists and athletes. (CEO Amy Hack wrote an open letter to singer Jax, thanking the singer for shining light on the brand’s errant ways through her hit song titled by its name.)

In I Need That, we explore how brands build meaning through who they exclude. But sometimes the excluded become more valuable than the exclusive.

The strategy is risky:

- Your loyal customers will feel betrayed

- Your new audience will need convincing

- Your brand meaning will shift dramatically

- And your short-term sales may suffer

But when it does work, it’s transformative.

Action for today: Look at who your brand might exclude. Are you missing a bigger opportunity by being too focused on your “ideal” customer?

Laurier

Product Payoff: When Converse‘s Chuck Taylor became popular with punk rockers instead of basketball players, the company almost fought it. Then someone pointed out that rebels buy a lot more sneakers than athletes!